Election Day is just around the corner, and the thoughts of many turn (perhaps reluctantly?) to politics. In a year when religious liberty has been an important issue, homeschoolers have an opportunity to draw lessons from history that can be applied to current events.

Election Day is just around the corner, and the thoughts of many turn (perhaps reluctantly?) to politics. In a year when religious liberty has been an important issue, homeschoolers have an opportunity to draw lessons from history that can be applied to current events.

And if you know where to look, there are excellent videos to supplement such study.

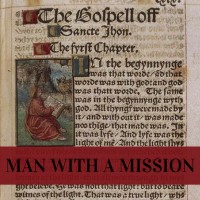

One such video is William Tyndale: Man with a Mission, a documentary film about the man who first translated the Bible into English.

Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament first appeared in 1526. But in an election year, it is Tyndale’s dealings with the political authorities of his day that provide reflection and application for our study of modern politics.

Man with a Mission admirably covers the history of Tyndale’s story with the assistance of Tyndale scholar Professor David Daniell.

Professor Daniell points out that Tyndale, though a loyal Englishman, fell afoul of the political authorities of his day. Why? Because “it was illegal in England to translate any part of the Bible into English.” Tyndale was obliged to operate covertly, “under guise of a scholarly study,” and eventually departed the country for Germany.

“Tyndale, as he left England…was breaking the law, and…knew it,” Daniell notes.

But he wasn’t the only one. Those eager for Tyndale’s English Bible were also complicit: “there were thousands upon thousands of people waiting in England…to buy it.” And 20,000 smuggled copies were purchased in England in the first eight years.

Tyndale’s fortunes would rise and fall over the next decade, but eventually, betrayed, imprisoned, and condemned for “heresy,” he was strangled and burned at the stake.

Why did he do it? In a conversation with a priest who had said people would be better off without God’s laws than those set up by the church, Tyndale replied, “If God spare my life, ere many years, I shall cause the boy that driveth the plow to know more of Scripture than thou dost.”

William Tyndale’s last words were, “Lord, open the king of England’s eyes!” These words were faithful, hopeful—and prophetic. Within ten months of Tyndale’s death, King Henry authorized a translation of the Bible into English. And when King James authorized his famous English translation the following century, one of the main sources the translators drew from was the English Bible of William Tyndale.

“The English Bible was made in blood,” Daniells reminds us. But Tyndale was ultimately victorious over his enemies, even in death. For all our problems, we remember that, “What Tyndale opened has never been shut up since.”

The lessons are numerous, but two will suffice: first, we must do always what is right, even when the pressure of culture and community are against us.

Second, we must labor and pray hopefully that God would open the eyes of our rulers. William Tyndale saw beyond the tragic end of his own life to a time when the Bible would be available to all his countrymen in their own tongue.

Above all, William Tyndale: Man with a Mission, is a message of hope—hope that the future will be brighter than the darkness of the present.